The world is waking up to the threat that ocean acidification (OA)—a rise in the acidity of seawater caused by excess carbon dioxide entering it from the atmosphere—poses to marine ecosystems and to the coastal economies that depend on them. Since OA’s damaging effects on shellfish were first documented 15 years ago, research organisations have mobilised to collect, on an ongoing basis, huge volumes of OA-related data from the world’s oceans. Based on those data, as well as data gathered in coastal areas, scientists have published a wealth of studies examining the causes and effects of OA.

Environmental advocacy groups championing ocean health, charitable foundations and intergovernmental organisations have built on this work to raise global awareness of OA, fund wider research into it and prod governments around the world to take concrete actions to combat it.

Governments, however, have been slow to rise to this challenge. Although many have voiced concerns about OA and expressed an intention to fight it through international mechanisms, at the time of writing less than a dozen have published dedicated action plans. These document specific measures governments will take—or are taking—to advance understanding and the domestic response to OA.

The experts we interviewed for this report are strong advocates for OA action plans. Measures to address OA have a vital place in wider climate change and other marine management initiatives, but a dedicated OA plan stands a better chance of cementing the ambition and commitment of a country, region or locality to actively address localised manifestations of OA and turn back the tide. And while some non-government organisations (NGOs) and science institutions have issued OA action plans of their own, none will carry as much weight as those led by governments.

National action plans are highly desirable, but it is state governments on the US Pacific coast that have set the standard of OA action for the rest of the world to follow. It is here that scientists first registered the deadly impacts of OA on marine life and the threat to coastal economies and jobs. That emergency and follow-on research findings led governments in the region to commit unequivocally to combat OA with the help of dedicated, detailed and well-resourced action plans.

In examining governments’ and other entities’ progress on mobilising against OA, this report finds that existing North American action plans offer useful examples and insights for other jurisdictions. Far from all governments will be able to base their plans on the same depth of research or call on the same resources to draft them. But by including in their plans elements such as a vision of success, timelines, assignment of ownership, and a mandate for periodic review and updating, governments can call upon more resources and put their OA action plans on a firm footing.

Ocean acidification is a growing threat to many forms of marine life and to the communities that rely on them for food, jobs and economic wellbeing. OA is a direct result of the growing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions generated by human activity. Up to 30% of carbon released into the atmosphere each year is absorbed by the ocean, which helps to mitigate global warming. But the ocean’s ability to sequester carbon cannot keep pace with rising emission volumes.1 The result is a decline in the pH level of seawater and a rise in its acidity.

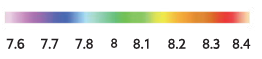

Figure 1: Ocean pH is falling

The pH level of seawater is a key indicator of ocean acidification. The pH scale runs from 0 to 14.

Over the past century, the mean surface ocean pH level has fallen from 8.2 to below 8.1.

About half of that decline has occurred in the past 40 years – a sign that acidification has been accelerating.

pH stripes for the global ocean (65°S - 65°N) with interannual and seasonal variability

Source: Data and timescale image from ETH Zurich

But pH is already lower than 8 in some waters, especially along some of our coasts. If global carbon emissions continue to increase at their current rate, by 2100, pH will be below 8 in most of the ocean.

Maps of sea-surface pH from the pre-industrial era to the future

Source: Courtesy of Andrew Yool. Adapted from HS Findlay and C Turley 2021. Ocean acidification and climate change. In: TM Letcher (Ed), Climate change: observed impacts on Planet Earth (Third Edition)

The detrimental impacts of acidification are more than scientific speculation. It is known to have a damaging impact on marine organisms such as oysters, mussels, scallops, crabs and other shellfish. In the Pacific North-west, large-scale losses of oyster larvae in 2007-08 were found to be tied to a rise in the acidity of hatchery waters. More recently, scientists have connected OA to weaker larval shells of Dungeness crab in waters along the US Pacific coast, negatively impacting the organisms’ growth and threatening a valuable source of aquaculture revenue. And recent reports from the north-east Atlantic region show negative impacts from increasing OA on Atlantic cod and cold-water coral reefs, critical habitats for regional fisheries.

Should CO2 emissions remain at current levels, one study has found, the concomitant rise in ocean acidification would put pteropods, bivalve molluscs, finfish and warm-water corals, among other types of marine organisms, at a very high risk of damage by the end of this century.

The threat that OA poses to biodiversity, food chains and economies is an integral part of what the UN describes as an ocean emergency. It is the reason that the UN calls for action to combat OA as part of its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly as captured in SDG 14.3.